Millennium Project

The Oxfordshire ironstone enquiry of 1960

Ironstone (technically Marlstone rock) was first recognised as an iron ore at Fawler (west of Stonesfield) in the 1850s by the British Geological Survey1 and was worked from about 1859. The Marlstone had been used for building from 'time immemorial' and its iron-rich nature must have been pretty obvious to anyone. Economic working would have been a non-starter, even in the days when transport was difficult, as very much richer ores were available in other parts of the country.

There had been no working on the scale proposed in the fifties. The issues were complicated and there were two public enquiries, in part because the company promoting the scheme does not seem to have anticipated any serious oposition and prepared its case so badly that the first enquiry was stopped.

There might have been an attitude that the scheme would inevitably go ahead as the applicant (the Dowsett Mineral Recovery Co Ltd) had been bought by Richard, Thomas and Baldwin Ltd, who were a 50% nationalised steel company. Thus the scheme was effectively being promoted by one Secretary of State and would be judged by another.

Ordnance Survey mapping © Crown copyright. AM130/04

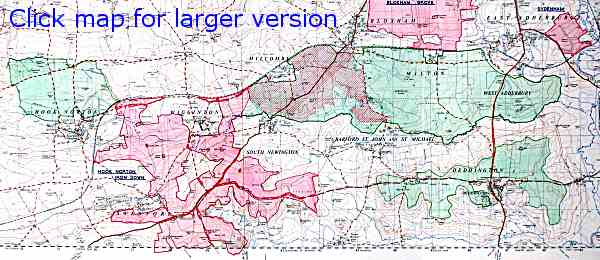

The map above shows the area for which applications were being made. The original was hand-coloured, for the enquiry; the pink area was to be mined first (mainly from Bloxham to Hook Norton) while the green area (including Deddington and northwards to Adderbury) was to be stripped later: literally stripped, as this was to be open-cast mining to a depth of about 30 feet. After the ore had been removed the top-soil would have been replaced and the land 're-instated' in the way that is familiar north of Banbury with the fields lowered and hedges standing proud on sharp embankments. The open-cast mining was due to last for 30 years or so and ironically would have come to an end at about the same time as the purpose-built mill in South Wales closed down.

Needless to say the countryside would have been devastated by the operation, and the noise, dirt and disruption would have been terrible. One of the documents produced for the objectors shows that in the Hook Norton and Irondown Hill areas no less than 1,750 acres of the application area of 2,550 acres would have been strip mined (708 of 1032 hectares). Initially the applications had been for only 185 acres east of Adderbury and 973 east of Bloxham - the thin end of a wedge.

It was very much due to the efforts of Major John Schuster2 of Nether Worton House and Major Eustace Robb of Tew Park that a fight was put up by no less than 20 local parishes, five boroughs, districts and the County. They were co-ordinated by the North Oxfordshire Area Protection Committee and joined at the Inquiry by other bodies including 44 WI branches, the Banbury Historical Society and many others. Perhaps the smartest thing the Protection Committee and County Council did was to commission the well-respected Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) to report into the scheme which it did twice in 19603. The Protection Committee not only raised funds to cover its own costs, but contributed over £1,000 to the County Council's costs.

The ultimate success of the objectors must be largely due to the fact that the EIU so clearly demolished the economics of the plan. However, even they were not confident that one minister would turn down another's project.

One of the more specious claims made by the applicants was that the area had no significant landscape value and thus was not worth preserving. The campaigners commissioned photographs to disprove this, eight of which were reproduced in 224, the newsletter of the Deddington & District History Society, with the whole set available here. NB the linked page contains many large images.

As can be seen on these pages the landscape photos presented to the enquiry and taken by W R Bawden of Eagle Photos of Cheltenham4 give the lie to any idea that it lacked value. More were commissioned from Blinkhorns of Banbury5 to show the effect of large-scale mineral workings in the area. Inevitably the former are the more attractive, especially as it would not have been appropriate for them to have dramatised existing ironworkings: they simply show the devastation in its drabness and simplicity.

I have been able to identify the location of most of the images, but there are still some that you may be able to help with. My contact details, if you can add any information on the photos, are below.

To quote Major Schuster, 'Rarely can a countryside have been more united or worked more closely together under the leadership of its County Council. This unity of purpose was, of course, founded on a deep appreciation of the countryside threatened, but it owed very much to the theme behind the local case, which was not a thoughtless "extract iron-ore from any contryside but ours" but rather "take this iron-ore from this countryside, much though we love it, if it really is in the national interest, but first you must show this, convincingly, to be so".'2

Colin Cohen, cohen@nehoc.co.uk

Notes

- Memoirs of The Geological Survey of Great Britain, The Mesozoic ironstones of England, The Liassic ironstones, T H Whitehead et al. London, 1952. I am indebted to Mike Sumbler of The British Geological Survey for his advice.

- I am most grateful to the Hon Mrs Lorna Schuster for making her late husband's enquiry papers available to me.

- A survey of sources of supply of iron ore to the United Kingdom and A study of the factors bearing on the decision whether or not to undertake large scale iron ore mining in North Oxfordshire, Economist Intelligence Unit. London, 1960.

- I have used 'best endeavour' to trace them, but have been unable to do so.

- I am grateful to Blinkhorns for permission to reproduce their photos.